Flags: When Patriotism Becomes Politics

Written by Hannah Wilson

Founder and Director of the Belonging Effect (formerly Diverse Educators).

We have all seen them. Driving up the motorway, crossing a roundabout in town, suddenly there it is: the Union Jack, or the red-and-white St George’s Cross, flapping over a bridge or painted over the crossing. No football tournament, no royal celebration – just flags, bolted into the landscape.

Let’s be clear – they are not innocent festive decorations (although some people are pretending/ or are naively thinking that they are in support of the World Cup Rugby and the UK Women’s team, the Roses). They are bold political statements.

On a Personal Note

I was back on the road for the start of term INSETs this week and as I drove from Bath to Worcester to Manchester to Matlock back to Bristol and then home to Bath, I lost count of how many flags I saw. I would guess 150-200 flags heading North and the same again heading South. It was noticeable which regions had a higher density and where they felt angrier in their positioning.

As I drove to a school in Manchester on Friday morning to join a MAT’s new staff induction day I felt sick to the pit of my stomach as I approached the school – they were everywhere, on every lamppost, gate and fence.

The sense of unease did not leave me all day. It felt hostile and threatening, despite them not being aimed directly at me. So, I asked the CEO and Executive Team of the MAT if I could speak to the elephant in the room, as I was concerned for the psychological safety of the staff who were gathered in the theatre, a visibly diverse workforce, many of whom had travelled from out of region. They agreed. They later asked me for some advice on how to navigate the start of term with the increasing tensions. I have been thinking about it ever since and what I would do if I was going back to being a school/ trust leader this week.

From Bunting to Battle Lines

In the past, flags have been raised for a coronation, for the Jubilee, or when England is playing in a World Cup match. The flags meant celebration, collective cheer, and coming together as a community, united through the event or the love of the game.

Now? The flags have become a different sort of shorthand. Reform UK supporters and far-right groups have learned that flags are cheap, visible, and impossible to ignore. Hang a Union Jack on a motorway bridge and the daily commute has been turned into a stage for politics.

My fear? How long will it be until the flags become bolder and braver, until the swastikas appear, until the ‘whites-only’ narratives of racially segregated nations get scrawled as graffiti beside them?

Why Roundabouts and Bridges?

Because they are public, they are prominent, and they belong to no one in particular. A roundabout or a bridge or a lamp post does not in theory need permission. It is ultimately a free billboard – one dressed up as patriotism but actually conveying hate.

In conversations with others about the growing campaign and visibility, I have heard two new phrases in the last week:

“Going roundabouting” has become a new hobby – people are taking their partners and their families out on the weekends to support the campaign and spend the day painting the flag on empty canvases.

“Your xxx looks like they go roundabouting” has become a new slur – playgrounds and classrooms will be divided by those who support and those who oppose these territorial and divisive behaviours.

Start of Term

As most UK schools re-open for INSETs, induction days and start of term this week, this cultural shift across the nation matters for educators. Symbols carry lessons. The flag on a bridge is far from neutral. It is an explicit message: “This is ours.”

Depending on who sees it, it can feel like pride… or it can feel like a warning.

It might as well say: “We belong here. You do not”.

What does this mean for schools?

- Our Senior Leaders will need to be visible – out on the gates, being the gatekeepers to the school’s boundaries.

- Our Safeguarding leads need to be anchoring this in the start of term KCSIE updates.

- Our Site Teams need to be vigilant and see if they begin to appear as graffiti on tables, on walls in our schools.

- As educators we need to be checking in on the welfare of our pupils and their parents/ carers.

- As employers we need to be checking in on the welfare of our employees.

Patriotism or Exclusion?

This is the heart of the issue. For some, these flags are a rallying cry for “taking the country back.” For others, they are an unsettling reminder that national identity is being policed in plain sight.

Educators need to help young people ask:

- Who is claiming the flag?

- Who is being included, and who is being left out?

- When does pride tip into nationalism?

- Why do some groups use symbols instead of words?

- How do different flags make different groups of people feel uncomfortable?

We also need to acknowledge that it is difficult to talk about one flag without considering other flags. People will ask why it is okay to fly the Pride flag and not the St George’s flag. Or why the Pro-Palestine flags have been vetoed but the St George’s flag has been supported and stays up.

Pulling flags down is also not the answer, if anything it is the reaction some are looking for to then escalate things. As schools, colleges and MATs, we thus need to consider our approach and our standpoint to flags and we need to apply it consistently for all flags, for all groups.

Why It Matters in Classrooms

What is important to remember is that all students will see these flags – on the way to school, on TikTok, in the news. If we ignore them, we leave the interpretation to whoever shouts the loudest. By unpacking the symbolism, we show students how politics works in the everyday: not just in Parliament, but in the quiet tying of a flag to a lamppost.

Flags are not the problem. The problem is when they stop being about unity and become markers of division.

Last September, we started term with a sense of unease post the faith and race riots of the summer. This September, we start the new term with a sense of unease about flags being weaponised. Both make our school communities feel unsafe, excluded and leads to people questioning their place and sense of belonging.

Final Thoughts

If we ignore it and we do not speak up, we feed the problem.

Check out a blog by Bennie Kara called ‘Flying the Flag’ and a No Outsiders Assembly on flags by Andy Moffat.

You may also want to speak up by signing the Hope Not Hate petition against the biggest Neo-Nazi music festival in Europe being held in Great Yarmouth this weekend.

Teaching Ideas for: Flags, Symbols, and Meaning

1. Spot the Symbol

- Show images of flags in different contexts:

A street party with bunting

A football stadium

A motorway bridge with political slogans nearby - Ask: “What’s the difference between these uses? How does the same flag carry different meanings in each place?”

2. Timeline of the Union Jack

- Research the history of the Union Jack and St George’s Cross.

- Students create a visual timeline: how has the meaning shifted from empire, to WWII, to the 1960s mod culture, to football, to today’s political movements?

- Prompt: “Does a symbol’s meaning change with time, or do we change how we read it?”

3. Bridge or Billboard?

- Debate exercise:

Group A argues that putting flags on roundabouts/bridges is legitimate free expression.

Group B argues it is intimidation or exclusionary.

Group C acts as judges, deciding which arguments were strongest. - Reflect afterwards: “How do we balance free speech with community impact?”

4. Flags Without Words

- Discuss why groups use flags instead of leaflets, speeches, or adverts.

- Activity: students design a non-verbal symbol or image to represent a cause they care about.

- Prompt: “What does your design say, and how might others read it differently?”

5. Critical Media Watch

- Collect recent headlines or social media posts about flags and patriotism.

- Analyse language: is the coverage celebratory, critical, neutral?

- Prompt: “How does the media shape whether we see flags as pride or protest?”

6. Personal Reflection

- Journal exercise: “When have you seen a flag displayed in public? How did it make you feel? Did you feel included, excluded, or indifferent?”

- Emphasise that different reactions are valid — it’s about recognising diversity of perception.

These activities help young people see that symbols are never neutral. They are tools of communication, belonging, and sometimes exclusion. The aim is not to tell students what to think, but to give them the vocabulary to analyse and question what they see.

Recommended Reading & Resource List

Articles & Commentary:

- The Guardian – “The strange politics of flags” (2021) – Explores how Union Jacks have been co-opted into culture wars in the UK.

- BBC News – “Why England’s flag is so divisive” – A short explainer on the St George’s Cross, from football pride to far-right appropriation.

- The Conversation – “Flags and nationhood: who gets to own national symbols?” – Academic but accessible, good for educators to unpack.

Books:

- Michael Billig – Banal Nationalism (1995)

Classic text on how everyday symbols (flags, weather forecasts, sports) quietly reinforce nationalism without us noticing. - David Olusoga – Black and British: A Forgotten History. Not about flags specifically, but brilliant for context on who “belongs” in British identity, and how that story gets told.

- Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger – The Invention of Tradition (1983). Explains how many “ancient” national symbols are surprisingly modern constructions.

- Khalid Koser – International Migration: A Very Short Introduction. Short and sharp, useful for helping students understand the backdrop to debates about identity and belonging.

Reports & Teaching Resources:

- British Future: “How to talk about immigration and integration” – Practical, non-partisan strategies for teachers and facilitators.

- Hope Not Hate: “State of Hate” reports – Annual overviews of far-right movements in the UK, including use of symbols and flags.

- Facing History & Ourselves – Lesson plans on symbols, propaganda, and identity that can be adapted for UK classrooms.

Multimedia:

- Podcast: Talking Politics – History of Ideas (episodes on nationalism and identity).

- BBC iPlayer: Who Owns the Flag? (documentary on the contested meanings of the Union Jack).

- YouTube: Vox – “The surprising history of the American flag” (useful comparison point; shows how symbols shift with politics).

These resources and readings can help educators:

- Ground classroom discussion in research and history.

- Show that debates about flags are not new, but part of long struggles over identity.

- Give students a bigger toolkit for thinking critically about the symbols they see every day.

Courageous Conversations

Written by Hannah Wilson

Founder and Director of the Belonging Effect (formerly Diverse Educators).

What is a Courageous Conversation?

In courageous conversations, whether in the context of performance appraisal, mentoring, or coaching, individuals are encouraged to express their views openly and truthfully, rather than defensively or with the purpose of laying blame. Integral to courageous conversations is an openness to learn.

What Is an Example of a Courageous Conversation?

Typical examples include handling conflict, confronting a colleague, expressing an unpopular idea on a team, asking for a favour, saying no to a request for a favour, asking for a raise, or trying to have a conversation with someone who is avoiding you. Research shows that many women find such “courageous conversations” challenging.

How Do You Frame a Courageous Conversation?

- Set your intentions clearly.

- Create a container.

- Prepare facilitators & groups.

- Set it up.

- Open with vulnerability.

- Have the discussion.

- Come back together and close.

- Support each other.

What Does the Research Tell Us About Courageous Conversations?

According to the work of Susan Scott there are The Seven Principles of Fierce Conversations:

- Master the courage to interrogate reality. Are your assumptions valid? Has anything changed? What is now required of you? Of others?

- Come out from behind yourself into the conversation and make it real. When the conversation is real, change can occur before the conversation is over.

- Be here, prepared to be nowhere else. Speak and listen as if this is the most important conversation you will ever have with this person.

- Tackle your toughest challenge today. Identify and then confront the real obstacles in your path. Confrontation should be a search for the truth. Healthy relationships include both confrontation and appreciation.

- Obey your instincts. During each conversation, listen for more than content. Listen for emotion and intent as well. Act on your instincts rather than passing them over for fear that you could be wrong or that you might offend.

- Take responsibility for your emotional wake. For a leader there is no trivial comment. The conversation is not about the relationship; the conversation is the relationship. Learning to deliver the message without the load allows you to speak with clarity, conviction, and compassion.

- Let silence do the heavy lifting. Talk with people, not at them. Memorable conversations include breathing space. Slow down the conversation so that insight can occur in the space between words.

Research Assumptions: Collaboration with The Centre for Education and Youth

Written by Alix Robertson

Associate at The Centre for Education and Youth

A decade ago, a Canadian professor of human evolutionary biology named Joseph Heinrich published a paper with the curious title: ‘The weirdest people in the world?’.

The study explored how behavioural science was dominated by the perspectives of researchers who drew on samples from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. It has often been implicitly assumed that the results produced from working with these groups are as representative of the human species as any other population.

But are researchers justified in making this assumption? Heinrich and his colleagues, psychologists Steven Heine and Ara Norenzayan, pursued this question by carrying out an empirical review of studies involving comparative experimentation on important psychological or behavioural variables. While not all research is created equal, the study was published in the international journal ‘Behavioural and Brain Sciences’, as well as in the renowned British scientific journal ‘Nature’, and Henrich went on to develop the idea into a book that was released this year.

The researchers reported that findings based on ‘WEIRD’ subjects are actually particularly unusual, compared with the rest of the human species, across a range of areas including fairness, cooperation, reasoning styles and self-concepts. The study suggested that members of WEIRD societies, including young children, are among the least representative populations when it comes to generalising about humans. Heinrich concluded that “we need to be less cavalier in addressing questions of human nature on the basis of data drawn from this particularly thin, and rather unusual, slice of humanity”.

Given these findings, the team at CfEY are keen to use our expertise in research to support Diverse Educator’s goal of improving diversity, equity, and inclusion in education. To do this we will be acting as ‘ambassadors’ helping DiverseEd to establish its own research strand, made up of studies carried out by or focusing on groups within DiverseEd’s nine categories of protected characteristics – and beyond.

To kick start this work we have contributed some of our existing research to seed the collection and we look forward to supporting DiverseEd in growing this bank in future.

- Encountering Faiths and Beliefs: The role of Intercultural Education in schools and communities – a report with Three Faiths Forum (now The Faith & Belief Forum) outlining the key principles of Intercultural Education and offering insights into how these principles can be adapted to suit different settings’ needs.

- Special educational needs and their links to poverty - a report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation showing close links between children having SEND and growing up in poverty; as well as the additional barriers these children face in accessing the support they need.

- Ethnicity, Gender and Social Mobility – a report for the Social Mobility Commissionin collaboration with Education Datalab, which explores how ethnicity, gender and poverty interact to support or constrain young people’s social mobility.

- Progression to University by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Pupils - a report in partnership with Kings College London’s Widening Participation department, which reveals the barriers ‘at every level’ that combine to make Gypsy, Roma and Traveller pupils one of the most under-represented groups in UK universities.

- A Place to Call Home: Understanding Youth Homelessness – research undertaken in partnership with the Sage Foundation, looking at how youth homelessness and education interact, and different ways in which the education system can support young people at risk of becoming – or who are – homeless.

- Schools and Youth Mental Health: A briefing on current challenges and ways forward – a report with Minds Ahead examining the scale and severity of the UK’s Youth Mental health crisis.

- ‘Boys on Track’: Improving support for white FSM-eligible and black Caribbean boys in London - a report with the Greater London Authority looking at how support for white free school meal-eligible and black Caribbean boys across London can be improved.

- Special or Unique - a report from Disability Rights UK and CfEY that explores young people’s attitudes towards disability and young disabled people’s experiences of school.

- Representation, engagement and participation: Latinx students in higher education - a report with King’s College London, examining the representation, engagement and participation of Latinx students in higher education.

We hope that these examples of our work will inspire others to join in with this exciting initiative. At CfEY we apply a critical lens to everything we do, and while anyone who is interested will be free to submit their research to the collection, we encourage the sharing of robust findings. By contributing quality work on the important themes that DiverseEd spotlights, you will be helping to build up a growing bank of studies that will encourage readers to think carefully about diversity and equality, and how they can drive improvements in representation.

Watch out for two events Diverse Educators (with support from the CfEY) will be running early next year to introduce the DiverseEd research strand.

Don't Tuck in Your Labels

Written by Bennie Kara

Co-Founder of Diverse Educators

Written January 7, 2018.

I am the woman that always has a clothes label sticking out somewhere. In any given day, some kindly person will reach behind me and tuck it in. And I, without fail, will apologise for that label and the fact that someone had to decide what to do with me.

You see, clothes labels are really useful things. They tell you what to do with the item. How to take care of it – how to fix the item if it is damaged in some way. It stays there as a reminder that the item needs to be nurtured. Lots of us become irritated by them – how many times have we cut the label out because we can’t forget it is there – perhaps it’s rubbing against our skin, making us feel uncomfortable. I do it all the time with the vain hope that people will not have to fix me up and make me presentable.

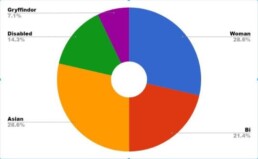

I have made many jokes over the years at various conference about winning the competition on how many labels I have. We categorise people in so many different ways and I have seen it as a laughing matter. So when I was thinking about my labels, I decided to create a pie chart of the make up of me. Mostly just in case my Maths teacher is watching – my Maths GCSE started with 30 mins of me panicking because I had forgotten how to draw a pie chart.

So if you want to see what my clothes label says – this is me.

It took a long time to decide how much of me I could allocate to the different labels. I am a woman. Quite considerably so, according the number here. I am also equally Asian. It gets harder when I have to decide just how much of me is on the LBGT spectrum. I define as bisexual and have been in a relationship with a woman for a long time. All of these categories I have become comfortable with – while I know they present me with challenges, I have spent my life getting to know them.

I have come to know myself as a Gryffindor too. This is not in jest. I will not have anyone disagree. I’ve taken the test.

It is my last label that is more recent and perhaps the one I struggle with the most. I learned not long ago that I have hearing loss in both ears and it is more pronounced in my left ear. I will be wearing a hearing aid soon to help me function in loud spaces, to help me understand what people are saying when I can’t see their faces.

I mean, I know I’m a woman and can’t lift heavy things or be in charge of a boardroom. I know that I am Asian and therefore should probably be teaching Science and not English. I know that I am bisexual and this means I am greedy/just not willing to admit I am gay.

But I was not prepared to be disabled, albeit in a small way. In some ways I have to confront here my own misgivings about having a hearing impairment in a profession that is built on listening to children in order to teach them. I sat in a car park and cried. Because this female, Asian, bi person didn’t want another label – especially one that could literally mean people think I cannot do my job. How many glass ceilings for me?

It has taken time to adjust to it. It chafed. I could feel it rubbing. But I have left it there because it gives people another way to know me.

Some people will say: if we take away all labels, we can just be people. I absolutely agree. I want to be able to teach without any of those. At the risk of sounding like a below the line Daily Mail commentator, stop going on about your labels – it creates the victim complex. It’s not important to the way you teach, so just shut up and get on with it. Identity politics creates resentment. I resent you and your labels.

I don’t think any of us walk around with our labels on our sleeves. If teaching is a profession in which your authentic self is required for children and adults alike to connect and know you, if it a profession in which people are the centre then I do not want to lie, either overtly or by omission.

The average 18-44 year old lies twice a day. I am sure that you are sitting there thinking – well that’s low. I can smash that statistic by 9am in the morning on any given school day. But the lies I tell because I have to are now starting to grate.

There are things I can’t say, choose not to say, places I won’t ever visit with my partner – and it is exhausting making all of those decisions about who I can be when I am simultaneously juggling the demands of the curriculum, behaviour, marking, meetings, paperwork. Wouldn’t it just be easier for me and more real for the students if I didn’t have to think about my pronouns so carefully? Or worry about who is going to see me with my partner in the local area?

I spoke recently about the curriculum and how having diverse voices delivering content doesn’t take away from what we teach our students – when we teach the Ramayana or about Malian women’s contributions to local industry, we are not saying do not teach about Wordsworth or Dickens. Perhaps as a female, Asian, bisexual, disabled Gryffindor, I can enrich rather than detract. Hiring me, allowing me to be free within a role, means a better education. Not because I am better. But because I can bring my knowledge and still teach yours really quite well. There is enough oxygen for all of our stories, told with pride. Authenticity in teachers allows students to understand humanity in all of its guises. We actively prevent learning when we lie, when we omit.

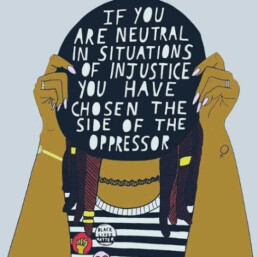

I have seen this quotation many times and it occurs to me that I no longer see it as being about other people. I see it as being about myself and about all of us that walk in different shoes. My silence about about me is collusion. I am colluding with the oppressor. It is unjust that I should be quiet, tuck in my labels to make everyone else feel comfortable, staff, students, parents alike. In remaining silent and not celebrating or sharing all of me as I am, I am complicit.

How can any of these things happen when we are silent?

I am not asking anyone to stand up and shout from the rooftops about their sexuality, disability, gender or heritage. But I am asking you to stand, metaphorically speaking. And speak about your truths without fear. And perhaps, when you feel brave enough because you have a room full of people willing to support you – to act, in the way that makes you feel that you are authentic.

So, if you see me again and my labels are sticking out. Maybe don’t tuck them in.

Closing keynote: Diverse Educators Conference, 6th January 2018